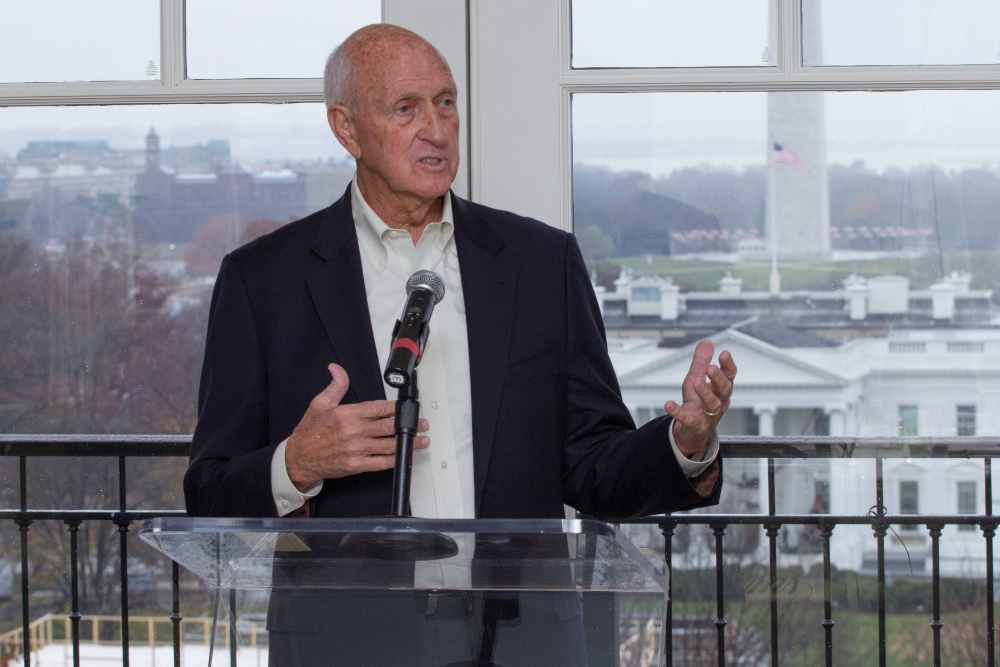

Almost three years ago, one of my mentors, Warren Rustand, spoke to an emerging group of leaders at Acceleration Partners as part of our advanced leadership training workshop. Rustand has built a storied career, serving as chairman or CEO of 17 companies, as a board member for dozens more, and even working in the White House with President Gerald Ford. Rustand generously spent two hours sharing many pearls of wisdom on principled leadership with members of our team.

Rustand’s speech left a big impact on the audience, in many ways. But in the months that followed, it became clear that one thing he said resonated most with the attendees. It related to how they should deploy their time and energy as leaders in their personal and professional lives. He said:

If you don’t control it, why worry about it? Because you don’t control it.

And if you do control it, why worry about it? Because you control it.

Since March 2020, many things have happened that feel completely beyond our control. However, we aren’t always honest with ourselves about where the marking of what we control begins and ends.

For example, let’s pretend you and I get into a minor fender bender one morning. As a grateful and enlightened person, you walk away from the accident feeling lucky the damage wasn’t worse and knowing you have insurance that will cover the costs. You arrive at work with that sense of gratitude, sign a new customer, have several productive meetings with your team and boss and go about your day as if the accident didn’t even happen.

I, on the other hand, love to play the victim. I am fuming about the accident–it feels like one more thing in my life I don’t need, and that negative attitude stays with me all day. I arrive at work agitated and end up driving away a prospect who senses my frustration and decides not to sign with me. Then, I get into a quarrel with my boss and am short with several colleagues throughout the day.

Neither of us could control getting into the accident in the first place (unless one of us was texting), but we certainly controlled what we did next, and our drastically different responses to the same initial incident resulted in very different outcomes for the rest of the day. This is an example of the value of emotional capacity, one of the four capacities I talk about in my book, Elevate.

A clear impact of emotional capacity is where we draw the line between what we control and what we don’t control. High emotional capacity helps us be resilient in the face of adversity by taking control of our reactions, while people with low emotional capacity more easily fall into helplessness when faced with those same challenges.

Emotional capacity variance is why some companies withdrew during COVID, refusing to change their ways, while others innovated and grew. It’s also why some people focused on themselves with a scarcity mindset and why others took on an abundance mindset and looked to help others.

Even as the pandemic slowly starts to abate in many parts of the world, the mental health impact from the strain of the past 18 months has clearly lowered our collective emotional capacity and ability to manage stress. Most people are understandably finding that they have a lower threshold for what level of stress becomes overwhelming, impacting their well-being.

Given that, it would stand to reason that one of the best ways we can improve our mental health is to give less energy to things that we don’t control and more attention to the things that we do. This means not getting overly emotional about the stock market, our favorite sports team, the weather, other people’s emotions, and other things that are out of our control. Instead, we should focus our time and energy where it matters and makes a difference.

What are you worrying about that you don’t control? How might it feel if you changed your approach?

Quote of The Week

“Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

– Author Unknown