We’ve completed two weeks of the National Football League season, and millions of football fans are playing fantasy football. Many fantasy managers are looking to add, drop or trade players to help improve their teams based on two weeks of data.

This is a risky time to be making these changes, however. What we’ve seen in the first two weeks of the season is not necessarily predictive of future performance.

For example, if we extrapolate the performance of some players after two games to an entire season, there are many players currently on track to annihilate statistical records. Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback Tom Brady is currently on pace to throw 76 touchdown passes, which would be 21 more than any quarterback in history.

Likewise, there are star players who are tracking to underperform their standard production levels by 80 to 90 percent because of two uncharacteristically poor games.

Fantasy managers tend to race toward overperformers and avoid or cut underperformers. However, the reality is these managers should be wary of reading too much into these extremes. While some early stars end up being breakout players for the entire season, and other players are beginning a long-term decline, the best strategy for many managers may be to bet against the outliers.

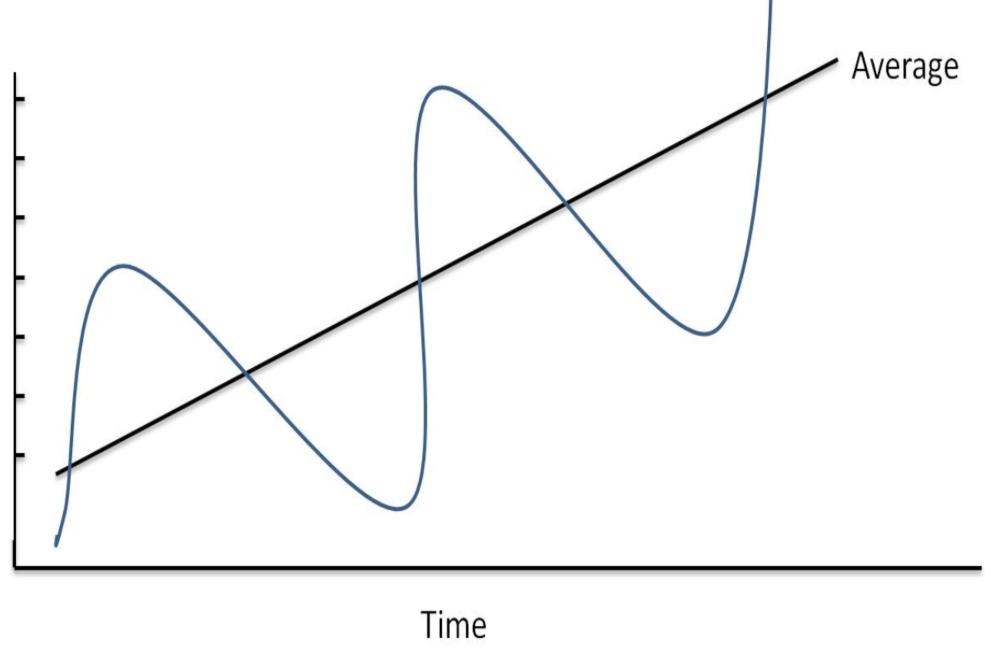

The reason for this is that, over the course of a full season, we are likely to see a regression to the mean.

The concept of regression to the mean was first discovered by the statistician and sociologist Sir Francis Galton. As part of his research, Galton observed that tall parents tended to have children who were shorter than them, whereas short parents often had children who were taller than them.

Based on this, Galton developed the principle of regression to the mean, which states that in any series with complex phenomena that are dependent on many variables, where chance is involved, extreme outcomes tend to be followed by more moderate ones. In other words, if something extremely unexpected happens, it is likely to be followed by something that’s more aligned with statistical projections or expectations.

We have a tendency to overreact to results in the short term and use those outcomes to make long term decisions, ignoring the reality of regression to the mean. In particular, we tend to ignore the role of luck and timing when evaluating extreme early outcomes.

For example, if I have a player on my team who has scored an average of eight touchdowns per 16 game season, and that player has scored four touchdowns in the first two games, that means he’s already halfway to his standard season average. I should not count on the player maintaining that performance, and should maybe consider benching him, as the probability of the player keeping up the same pace is much smaller than the probability that he will end up somewhere near his historical season total. He may even be about to enter a streak of subpar games.

Of course, the inverse is also true: a player on a cold streak is likely to return to their long-term average production in the future and therefore may even be due for a strong run of games.

Regression to the mean applies beyond fantasy football. It presents a distinct challenge for leaders who are trying to determine if something is the start of a long-term trend or a brief statistical aberration.

For example, anyone who has led a sales organization knows how much luck and timing can impact sales performance. In the short-term, overreacting to outlier performance can result in assigning too much credit or too much blame, especially to individual reps. A hot streak or a cold streak might have more to do with luck and timing, rather than indicating a longer-term pattern.

The trick for both leaders and fantasy owners is to better understand which aspects of improved or diminished performance are reliable indicators and which might be due to outside forces. It’s also important to look at historical data for context and for benchmarking.

One trend that we measure across many different departments in our business is the rolling twelve-month average, as it tends to be a better indicator of upward and downward trends and removes short-term aberrations that can cause panic or overconfidence.

Where might you be overreacting and making a choice that may look misguided once things regress to the mean?

Quote of The Week

“Mimicking the herd invites regression to the mean.”

– Charlie Munger