When the history books chronicle the last two years, we will learn about many crucial decisions that were made. We’ll see how many lives were saved with heroic and bold actions, and how some were lost because of decisions scuttled by incorrect assumptions, politics, misinterpreted data or even just poor timing.

As is often the case, these decisions will be evaluated with the benefit of hindsight, which is always a 20/20 lens. There will be an impulse to give more credit or blame than these decision-makers actually deserve, without factoring in the limited information available at the time, the impact of timing, or just plain old luck.

As a result, history will likely permanently enshrine or condemn many of the leaders who made these challenging and often real-time decisions. History is written by the victors.

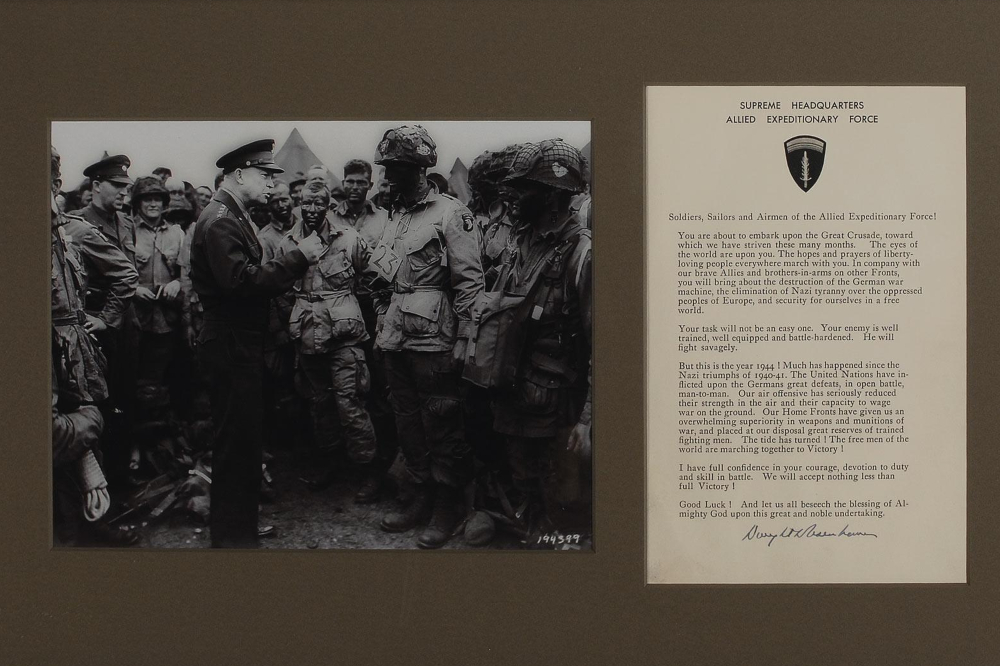

Two weeks ago, we commemorated the 77th anniversary of D-Day, the landing of the Allied forces in Normandy during World War II. The mission, one of the most important battles in history, was led by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, whose leadership on that day propelled him to venerated status and, eventually, the American Presidency.

Before the invasion, Eisenhower gave a now-famous speech to his troops to lift their spirits and display his confidence in a victory. In the speech, he remarked:

Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to Victory!

I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!

Reading this today, Eisenhower appeared certain his forces would prevail. But what is often left untold in history is that Eisenhower also wrote a second note the night he delivered his speech, which became known as the “In Case of Failure Letter.” The letter’s full text read:

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

Had just a few things gone differently on D-Day, Eisenhower’s “In Case of Failure Letter,” and not his speech, may have been the defining moment of his legacy. Nothing about the circumstances, Eisenhower’s leadership or his preparation for D-Day would have changed, but his story would have certainly been told very differently.

Eisenhower’s example offers a few key takeaways, nearly eight decades later:

- Great leaders give their teams credit for success and take sole responsibility for failure. This is a rare skill today. Many leaders, especially politicians, love the credit but hate the accountability. However, these are two sides of the same flipped coin.

- When evaluating decisions through the lens of history, we should ask: Was it a good or bad choice based on the available data at the time? Some people are celebrated for making decisions that worked out in their favor but would fail a vast majority of the time if repeated. Those lucky outcomes aren’t the decisions we want to emulate.

- We need to judge our own past successes and failures more objectively. We tend to believe that our achievements are due to our intelligence and smart decision-making, while ascribing others’ successes to luck and timing. What if the opposite is true? We should rethink those assumptions more often to avoid hubris and overconfidence.

It’s rare for us to scrutinize decisions that yield a positive outcome as rigorously as we consider the ones that do not. However, re-examining some our successful choices can often produce helpful learnings.

Leadership depends upon making tough decisions based on the best information available and understanding and owning the consequences of those decisions. It also requires realizing that the difference between making the right choice and the wrong one might have more to do with luck or timing than preparation and judgment, while knowing history will rarely view it that way.

Quote of The Week

“One of my predecessors is said to have observed that in making his decisions he had to operate like a football quarterback — he could not very well call the next play until he saw how the last play turned out. Well, that may be a good way to run a football team, but in these days it is no way to run a government.”

– Dwight D. Eisenhower