Wisdom is a bit like wine; while it often gets better with age, it sometimes turns unusable in the long run. Where we can get into trouble is when we declare something or someone brilliant before this aging process has fully played out.

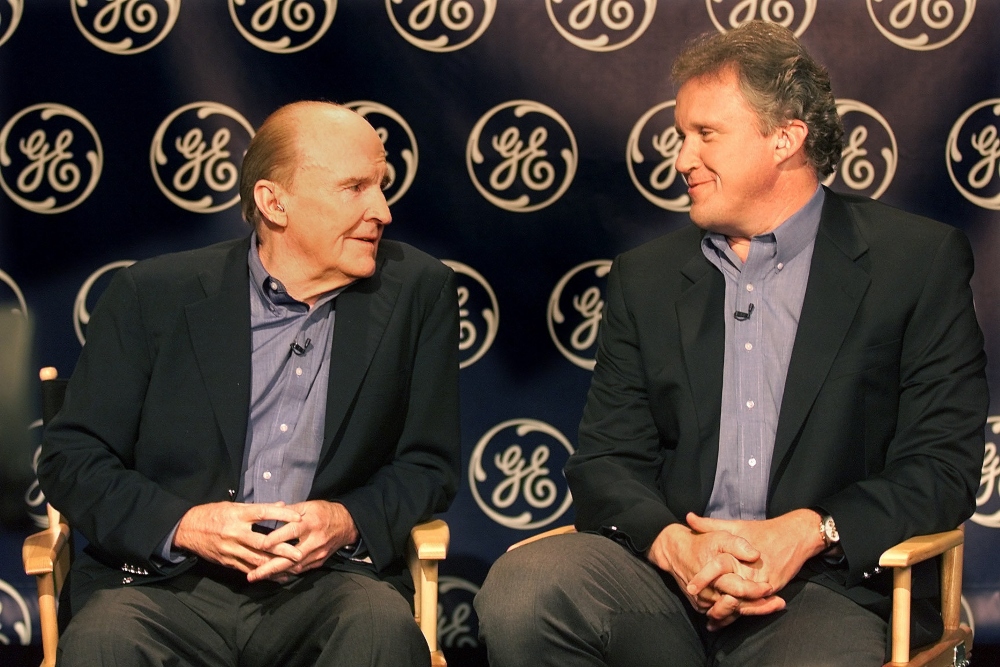

A strong case of this is the famous Jack Welch succession story at General Electric (GE).

Welch was an iconic CEO, responsible for growing GE from $12 billion in market value to $410 billion in 20 years at the helm. I was taking business classes in college as Welch was in the process of selecting his replacement as CEO. His succession planning was held up as a gold standard case study at every business school before he even made a decision.

Over a six-year search for his successor, Welch narrowed the race down to three handpicked finalists: Jeff Immelt, James McNerney and Robert Nardelli. As Welch considered himself a master talent evaluator and developer, he did not even consider an outside candidate.

When Welch selected Immelt for the CEO job, the succession process was heralded as a success and the details were shared widely for every company to emulate. But, through the lens of hindsight, the results were disastrous.

Immelt’s 16-year run as CEO was, at best, “controversial,” in his own words. When he left GE in August 2017, the company was drowning in debt, and its market cap had plummeted from $410 billion to $200 billion over his tenure.

It would appear Welch might have chosen the wrong finalist. However, his other two contenders don’t look any better than Immelt 20 years later.

McNerney left GE to become CEO of 3M. While 3M grew under his leadership, he left the company quite abruptly, disappointing the firm with his quick exit. He then served as CEO of Boeing from 2005 to 2015, where one of his most important priorities was the development of the 737-MAX airplane.

You may already know what happened next. Boeing was fixated on getting the 737-MAX to market as quickly and cheaply as possible, while avoiding costly federal oversight. The result of this was two fatal crashes that killed 346 people and resulted in the plane being grounded for over a year. That disastrous aircraft cost Boeing $55 billion in value and was a PR disaster the company is still digging out of today.

For his part, Nardelli left GE to serve as CEO of Home Depot, where he replaced the firm’s culture of innovative product design with one of intense cost-cutting. Nardelli was known for having an outsized compensation contract and a habit of alienating both employees and shareholders. The company’s price and market cap stagnated under his leadership, and Home Depot was surpassed by its top competitor, Lowe’s, during his tenure. He was pushed out of the company in 2007.

While these are cautionary tales of putting too much stock in untested wisdom, the opposite can be true as well. Sometimes the process is reversed: an idea or person is dismissed in the moment but is proven right in the long run.

In that same year that Nardelli departed Home Depot, an unknown first-time author named Tim Ferriss published a book called The Four-Hour Workweek.

The book was dismissed by many as a get-rich-quick book on marketing and outsourcing that was unrealistic for most people. However, for many people, including myself, the book announced a philosophical shift on how to live a more intentional and fulfilling life, and escape the nine-to-five. A core premise of the book challenged the notion of working hard and deferring enjoyment until retirement.

The Four-Hour Workweek has gone on to sell over 1.3 million copies in thirty-five languages, as I shared in the opening chapter of my own book, Elevate. Looking at the developments of 2021, Tim could not have been more prescient about the numerous changes we are seeing in the workplace today.

In the moment, it might seem easy to judge someone’s ideas as brilliant or foolish. But the truth is it might take years for either narrative to be proven true. While Jack Welch was a great CEO, he ultimately failed to develop a successful successor and it’s probably time we started teaching why and how his once revered process created three leaders who underperformed in their roles as CEO.

Quote of The Week

“Wisdom is like wine, it’s often hard to know the quality until it ages a few years.”