In 1999, researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger published a landmark study that revealed an unconscious cognitive bias now known as the Dunning Kruger effect. The Dunning-Kruger effect describes a situation where a person’s lack of knowledge or skill in a certain area causes them to overestimate their own competence or ability in that same field.

A classic example of the Dunning-Kruger effect is the case of McArthur Wheeler. In 1995, Wheeler attempted to rob two banks in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania after covering his face in lemon juice. Wheeler genuinely believed the juice would make him invisible to security cameras—during his trial, it was revealed that he had conducted his own “experiments” with lemon juice before the robbery, and became certain the juice would be an effective disguise.

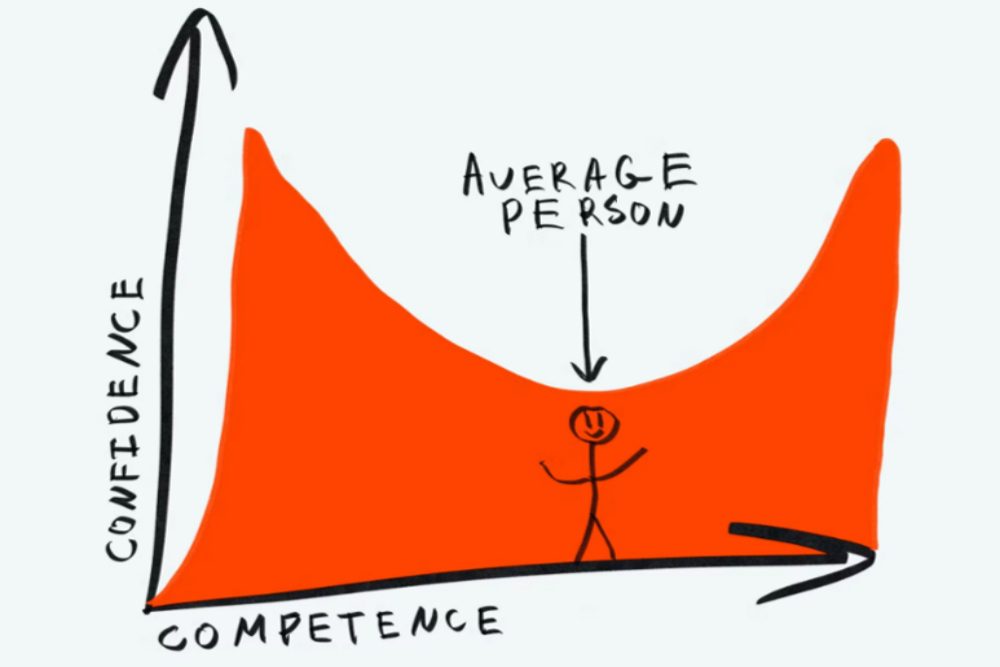

Along with their findings, Dunning and Kruger published a u-curve that plotted the relationship between competence and confidence. The u-curve shows us that, when people first gain basic knowledge or experience in a field, they tend to have far more confidence in their abilities than they should. A classic example of this is the college freshman who tells their hallmates they can master the stock market after two weeks of Intro to Economics.

Past that point of unearned cockiness, however, people’s confidence tends to grow more realistic. Dunning and Kruger found that individuals with moderate levels of ability in a field are actually more likely to properly estimate themselves. People with moderate levels of ability can better recognize their own limitations and mistakes; they know what they don’t know.

Finally, the u-curve leads us to the highest level of ability—these are truly knowledgeable experts who have a well-earned confidence in their capabilities. What’s most remarkable about the u-curve is learning that some of the least capable people have the same level of confidence as the most learned experts.

While the Dunning-Kruger effect was originally studied in relation to physical ability, it’s just as relevant in today’s information economy. This is especially true as more and more people obtain unvetted information from social media “experts,” rather than from trust-worthy, verified sources of news and expertise.

Having a large following does not necessarily indicate expertise or credibility on a topic. This applies not only to individuals who have gained a following despite lacking expertise, but also to people are well-regarded experts in one field, but express strong opinions on unrelated subjects where they lack that same level of ability or experience. This phenomenon is not limited to social media, as many individuals exhibit the same overconfidence offline when discussing subjects outside of their area of expertise.

Knowing this, it’s important to be cautious when seeking advice from experts on a topic outside of their specialized knowledge, as they may not be as well-versed in that area. For example, you may not want to trust financial advice from your pediatrician or medical advice from your financial advisor. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion; however, one of the major problems with information flow today is that we don’t really separate fact from belief. We often fail to make this distinction when we share our own thoughts, and when we read or hear others’ thoughts.

As McArthur Wheeler learned, people’s tendency to overestimate their own abilities due to a lack of knowledge or skills in a certain area can have enormous real-world consequences. This cognitive bias is something we should all be aware of when we are discussing and consuming information in the modern age, especially if we lead teams or organizations.

A good way to avoid this trap yourself is to keep an open mind, seek out diverse information and perspectives, and recognize that admitting what you don’t know can be a better indicator of your knowledge than giving an ill-informed opinion and assuming you are correct.

Quote of The Week

“The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.”

–Stephen Hawking