One of my favorite inventions of the past decade is a harness system designed for outdoor adventure parks. The harness has two separate clips, one of which unlocks only when the other is locked. This simple feature has led to an entire industry of self-guided ropes course parks where people can navigate courses without hands-on supervision.

What I love about these courses is while they preserve the feeling of discomfort, and just a bit of fear, the harness removes the possibility of serious injury, even for inexperienced users. I have really enjoyed doing them with my kids over the years, with one particular trip standing out in my memory.

On that day, my son, who was 10 at the time, and I tried a course that was more difficult than he’d attempted before. As he worked through one of the final obstacles, he hit a breaking point and suddenly panicked. On the verge of tears, he begged me to come help him.

I decided not to intervene, because I knew he was safe, and wanted him to have the satisfaction of pushing through a challenging moment. Instead, I encouraged him that he could do it and talked him through getting to the other side, ignoring disapproving looks from other parents present.

Not only did my son make it through without assistance, but on the next trip to that same course, he confidently led his friends through it, without needing me at all.

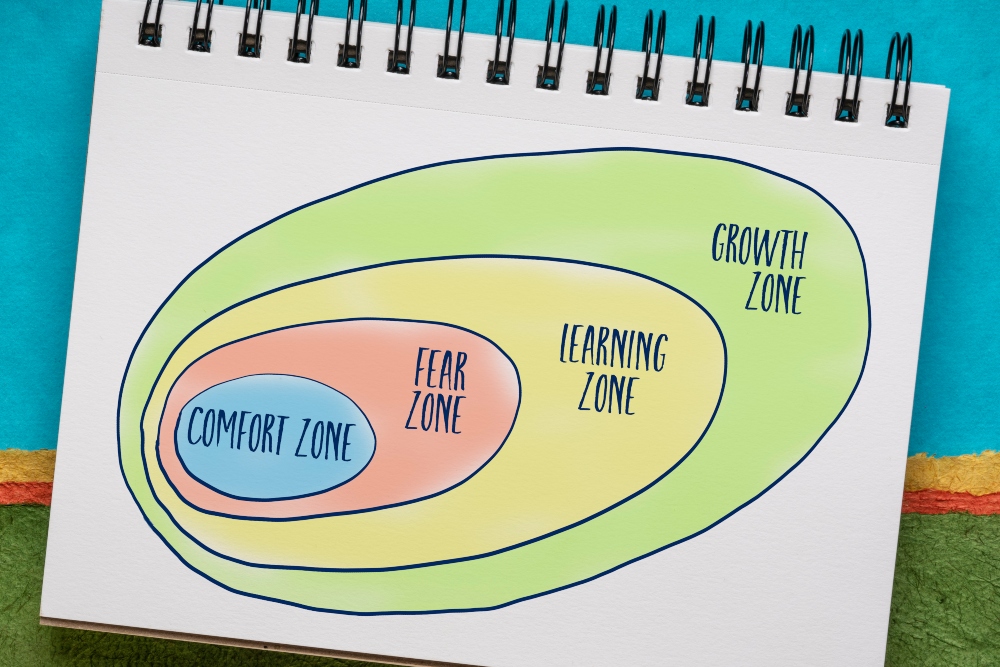

We constantly hear the best experiences in life happen when we’re outside our comfort zones. While we know this to be true, we often struggle to follow the advice when the opportunity presents itself.

Some risks and activities outside our comfort zone do come with real potential financial or physical downsides. But, more often than not, the only real risk we face is experiencing embarrassment or emotional discomfort. These are the risks we should always take.

It helps to think of risky activities and discomforting activities as two separate circles. Sometimes, they overlap, but more often than not they are separate.

For example, shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was generally considered unsafe to gather in public. This was a case where the risk and discomfort circles overlapped. Now, two years later, the risk and discomfort circles don’t overlap for most people, but you still may have felt some unease when you started resuming “normal” life as vaccinations increased and risk became less severe.

But even though the risk of contracting a serious case of Covid-19 has changed greatly for most people, many can’t shake the feeling of discomfort that comes with activities that were once considered highly risky. We struggle to distinguish between what’s actually risky and what’s just uncomfortable.

If you have an opportunity in your personal or professional life that is physically or psychologically safe, but has an element of discomfort, it’s worth trying to push through that discomfort. It can also be helpful to ask yourself why you are feeling discomfort two or three times to reach the source of your hesitancy. Doing this may unlock something deeper for you that has been holding you back in your career or personal life. Maybe you will find that in some capacity, you don’t want the world to see the real you. That fear, while understandable, will always hold you back in the long term.

In trying to understand the causes of the mental health crisis today, I have found a particularly resonant theme, aside from the rise of social media. Parenting has changed in the past few decades. Even though the world is less dangerous on an absolute basis, parents have shifted from letting their kids spend all day without supervision to actively managing their kids’ day-to-day activities and removing obstacles from their lives. While well-meaning, this parenting style prevents kids from experiencing and learning from failure and discomfort, which in turn lowers resilience.

Once these kids become adults, they find they don’t have the emotional capacity to handle the challenges of the real world on their own. Their circles of safety and discomfort fully overlap—discomfort feels like a mortal risk, rather than an opportunity.

This is why it’s so important to encourage kids, from a young age, to try hard things and learn to navigate situations that are uncomfortable, but ultimately safe. As leaders of organizations and in our families, it’s also important for us to model this behavior.

The next time you have an opportunity that is outside your comfort zone but physically safe, remember to ask yourself honestly why you are hesitant to jump in. The source of your fear might surprise you.

Quote of The Week

“The more you practice tolerating discomfort, the more confidence you’ll gain in your ability to accept new challenges.”

–Amy Morin